Studio Outside is pleased to share a conversation with Erin English, PE Practice Leader & Senior Engineer at Biohabitats, an ecological restoration and regenerative design firm that operates in various bioregions across the nation. Based in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Erin works alongside clients as well as landscape architects to advance innovation in nature-based infrastructure with a focus on water and ecology. Erin has led the construction of wetlands, wastewater, rainwater, and water reuse engineering for award-winning projects that achieved the Living Building Challenge™ and net zero water. Biohabitats recently received the ASLA Firm Award for 2023, highlighting that ecology has a powerful role in the planning and design of human places, communities, and regions.

sO: What got you excited about pursuing sustainable water management? What inspires your work and passion?

EE: I spent five years studying chemical engineering and started working for Dr. John Todd, the creator of the Eco-Machine™, designing with natural, living systems. That early work got me excited to take a unique path and find ways, as an engineer, to partner with nature.

sO: What are the challenges that you’ve faced during your time in this field?

EE: We have a responsibility to create safe and sustainable systems. You want it to fail safely if you fail. The biggest challenge is balancing looking to nature for a solution in a way that is safe for public health while not losing the ability to truly innovate using a natural systems approach. We all need to continue to learn how to reintegrate ecological systems into our infrastructure.

sO: Being based in New Mexico, a landscape that performs with little water, how has that shaped your approach?

EE: When traveling, I often get weird looks that a water engineer would live in New Mexico. I love working here because of the preciousness of water in this arid place. New Mexico has not experienced a huge population boom like Arizona or Las Vegas. Its strong land-based culture is credited to the Native American Pueblo and Northern New Mexican communities, which have informed much of my perspective on protecting and valuing water. It’s celebrated; it’s sacred. It’s important to have conversations about water conservation when building a city or development to make sure that it is respectful of the land and the ecology that it’s in.

sO: What has been a favorite project and why?

EE: The Kendeda Building for Innovative Sustainable Design at Georgia Tech in Atlanta. It’s the first Living Building in the South. It’s a university building used for classrooms and lab space in the middle of an old campus parking lot. The building is connected to an adjacent high-performance landscape called the “Eco Commons,” a ribbon of green infrastructure that Georgia Tech is revisioning as a core part of their campus’s response to stormwater management and combined sewer sheds. The project itself is net positive water and energy, treats all its own waste, harvests its own water, and vastly reduces stormwater runoff that impacts downstream communities and ecosystems. We had a great design team, and we were able to engage university students in the process. This shows that true ecological innovation can happen in the Southeast.

sO: Which sector, (public, private, non-profit), do you think will be the most impactful moving into the future?

EE: Most innovation comes from the private sector because it is nimbler and can move faster. I think that the private sector can do more and there is a growing need for that leadership. The work is gigantic! Getting ranchers and larger landowners on board could really move the restoration effort, and water efforts, forward. With over 95% of land in Texas being privately owned ¹, the responsibility falls largely to the private sector. It’s important to understand the place, look at what you have and the regional context around you and ask how your project can add to the ecology, and benefit the watershed-without taking anything away. Embedding this knowledge within the landscape is possible.

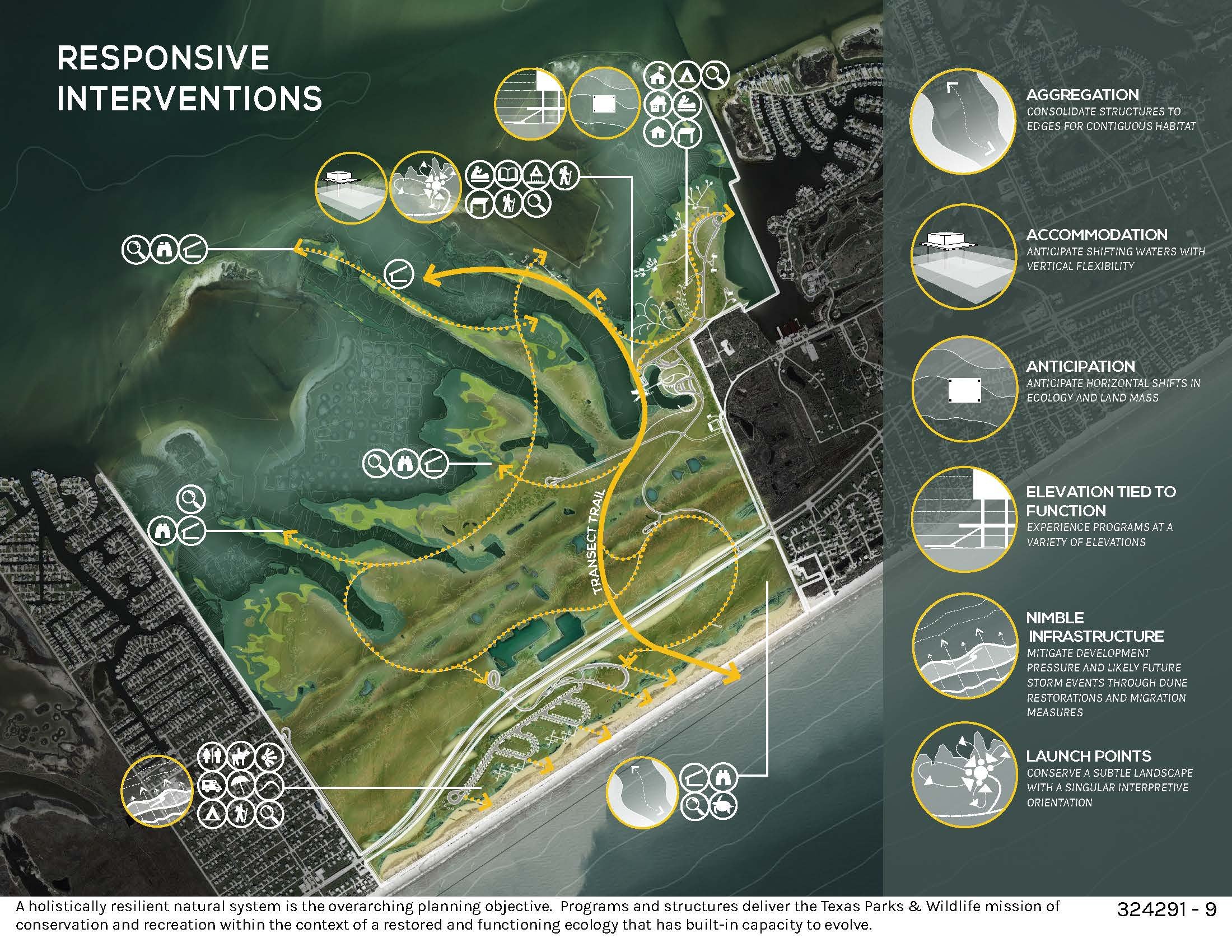

Studio Outside has enjoyed collaborating with Biohabitats on Galveston Island State Park and Iain Nicolson Audubon Center as well as many others across the country.